Essay for Material Light Kochi: In Praise of Shadows

Tanizaki’s famous essay, In Praise of Shadows was written in 1936 as a homage to the era immediately preceeding the full-scale introduction of the electric light, a development which was about to change the everyday experience of Tokyo dwellers for ever. This great piece of writing has lost none of its impact in that it still directs and instructs our gaze, gently guiding us in how we might perceive our surroundings. That such an engaging work should come from a meditation on change and obsolescence is one of the themes and inspirations for this exhibition.

Material Light examines ways in which new technologies redirect the means of artistic production, simultaneously adding new possibilities whilst reducing the elements of our vocabulary which have fallen into obsolescence. Some would argue that this has compromised our material engagement with the immediate environment.

The notion of the ‘paperless office’ sought to persuade us of the green credentials of the digital revolution. That the production and destruction of paper was in abeyance was seen as a good thing – more ecological, greener. Not only did the volume of paper documents fail to decrease, we now understand that the carbon footprint of the infrastructure required to support the on-line world, with its massive servers and cooling systems, is greater than that of the global aviation industry, not to mention the detritus created by the built-in obsolescence of all those laptops, phones and screens .

The notion of the ‘paperless office’ sought to persuade us of the green credentials of the digital revolution. That the production and destruction of paper was in abeyance was seen as a good thing – more ecological, greener. Not only did the volume of paper documents fail to decrease, we now understand that the carbon footprint of the infrastructure required to support the on-line world, with its massive servers and cooling systems, is greater than that of the global aviation industry, not to mention the detritus created by the built-in obsolescence of all those laptops, phones and screens .

It could be argued that analogue technologies are more focussed at the point of delivery whereas the physical materiality of the digital world is predominantly located in storage, networks and platforms. Much of the physical presence of online presentation is absented from the field of its operation, giving the illusion of immateriality, that is apart from screens, projectors, phones, tablets and cpu’s that carry the images and text.

That we are able to ignore the material embodiment of image-based technologies on such a vast scale recalls Roland Barthes comment that we are in general unaware of the photograph as physical object, as we are so swept up in the narrative it represents. His declaration in his 1980 work, Camera Lucida that; ‘Whatever it grants to vision and whatever its manner, a photograph is always invisible: it is not what we see’, seems not to acknowledge the years of modernism with their emphasis on the object or document as a fact in itself.

Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism and the rest, seem to have done little to reduce our blindness to the presence of the physical embodiment of photographic images.That we are somehow able to live in an ‘un-physical’ universe in which images and artworks are somehow introduced into our consciousness in a completely immaterial way, is an illusion. If images are apparently created without the substantial use of materials, they are certainly made visible and presented to us through the employment of very substantial technologies. Anxious to embrace the creative possibilities of the digital world and led by the imperative of the new, artists have been keen to engage in these new possibilities, whilst also sometimes being vocal in their critiques of the new environment. This exhibition raises some of these questions – whilst also celebrating the abstract potential of the analogue world and the many ways in which digital and analogue methodologies interact with each other. Layers, oxidation, accretion, patina and decay are the language of the analogue world. It is the language of geology, of libraries, of the periodic table, chemical variation and carbon dating. The accumulations of time recorded in the material substrates of our surroundings.

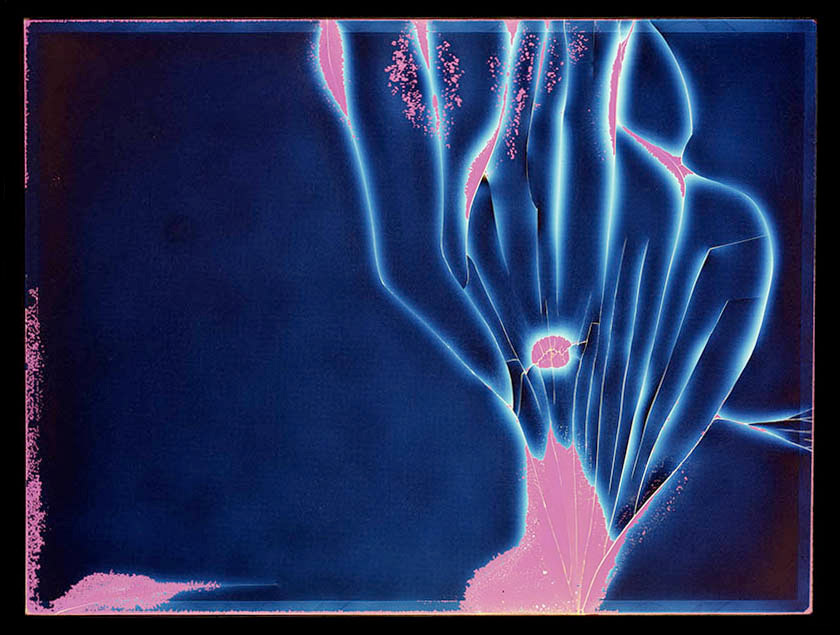

The digital world also has its own aesthetic and powers of enchantment. This aesthetic is often a ‘given’ – handed down fully formed by its providers. The ‘post-photography’ movement is in large part a response to this situation. Artists recognise that the digital world is also heir to obsolescence and decay and has its own language of stylistic choices, accidents and idiosyncracies. David Blackmore’s Liquid Crystal Displays, 5×4 transparencies of broken screens electronically re-animated for his large format photographs, point to this aesthetic, whilst reminding us that obsolescence is a continuous process – and that the future is always out of reach. The digital sublime instructs us in the images of numbers, how they can be assigned to both the minutest and the infinitely large aspects of our world, for example continuing photography’s ‘special relationship’ with astronomy.

The digital world also has its own aesthetic and powers of enchantment. This aesthetic is often a ‘given’ – handed down fully formed by its providers. The ‘post-photography’ movement is in large part a response to this situation. Artists recognise that the digital world is also heir to obsolescence and decay and has its own language of stylistic choices, accidents and idiosyncracies. David Blackmore’s Liquid Crystal Displays, 5×4 transparencies of broken screens electronically re-animated for his large format photographs, point to this aesthetic, whilst reminding us that obsolescence is a continuous process – and that the future is always out of reach. The digital sublime instructs us in the images of numbers, how they can be assigned to both the minutest and the infinitely large aspects of our world, for example continuing photography’s ‘special relationship’ with astronomy.

Sophy Ricketts Objects in the Field (2012) was made during a residency at the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University. The images she made there combine some of the last analogue images to be created at the institute with colour pallettes used in more recent false-colour images of deep space, originating from the Hubble Telescope. These deep-space images are gathered as data – emissions from different types of atoms – and need to be constructed as images to make them intelligible to the eye. The artist’s strategy references Elizabeth Kessler’s assertion that these colour palettes originate from the tradition of mid 19thC North American painting, for example in the work of Thomas Moran or Albert Bierstadt’s series of mid 19thC paintings of the American West entitled “The Westward March of Civillisation”.

Sophy Ricketts Objects in the Field (2012) was made during a residency at the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University. The images she made there combine some of the last analogue images to be created at the institute with colour pallettes used in more recent false-colour images of deep space, originating from the Hubble Telescope. These deep-space images are gathered as data – emissions from different types of atoms – and need to be constructed as images to make them intelligible to the eye. The artist’s strategy references Elizabeth Kessler’s assertion that these colour palettes originate from the tradition of mid 19thC North American painting, for example in the work of Thomas Moran or Albert Bierstadt’s series of mid 19thC paintings of the American West entitled “The Westward March of Civillisation”.

Apart from its infrastructure and mediums of presentation, electronic images eventually leave no trace – as long they survive they remain unaltered by the passage of time – something not lost on those who have made ill-advised contributions to the online world. But eventually they will dissipate in a flash of static, a once vital occupant of an obsolete platform.

Contemporary artists use found images and documents for a number of purposes. Photography is heavily predicated on the passage of time and the use of historical (analogue) imagery is one way of evoking or referring to the past. Some may say that any interest in analogue technologies is a commitment to nostalgia, but there are some effects which are impossible to realise without calling for material assistance and employing the aura which surrounds such artefacts.

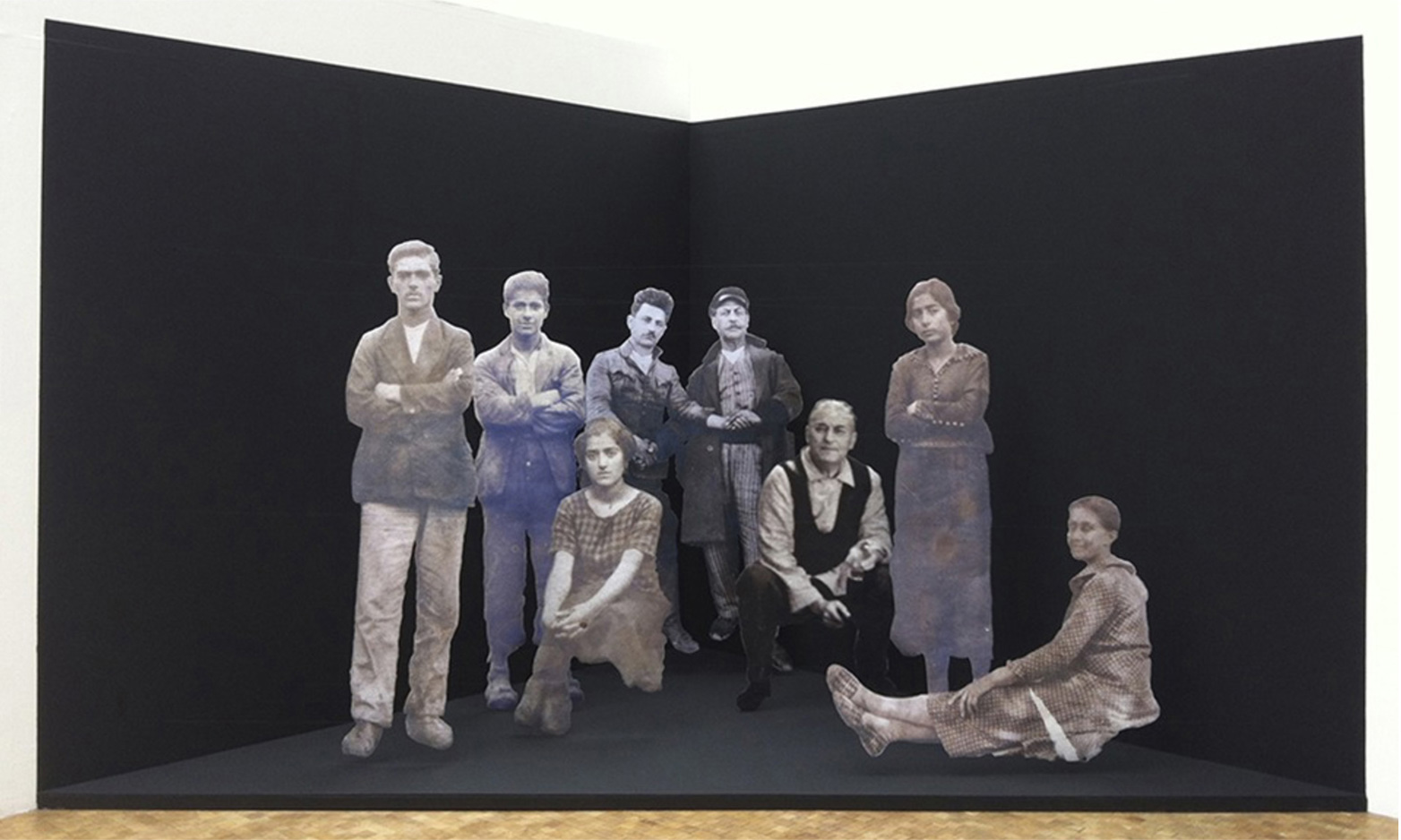

Armenoui Kasparian’s The Survivors employs snapshots of refugees from Armenia in 1917 enlarged to full sized figures which powerfully bring our attention to an historical narrative which is still unfolding in the present.

Armenoui Kasparian’s The Survivors employs snapshots of refugees from Armenia in 1917 enlarged to full sized figures which powerfully bring our attention to an historical narrative which is still unfolding in the present.

Whenever a new technique is instigated, existing methods are marginalised, and the resulting benefits derived from these new technologies are transferred to new beneficiaries. The conveniences we enjoy from digital media can mean that we are disadvantaged by the loss of old ‘goods’.

Nihaal Faizal’s Stolen is a 16mm film from which the image has been almost entirely stripped from the celluloid. The film, liberated from the Karnataka Documentary Film Archive, is a documentary of Indian independence activist and educator H. Narasimhiah, who appears as a ghost in this document of his own history. The resulting work is emblematic of the vast archives of material history which have failed to make the transition to digital formats.

Nihaal Faizal’s Stolen is a 16mm film from which the image has been almost entirely stripped from the celluloid. The film, liberated from the Karnataka Documentary Film Archive, is a documentary of Indian independence activist and educator H. Narasimhiah, who appears as a ghost in this document of his own history. The resulting work is emblematic of the vast archives of material history which have failed to make the transition to digital formats.

It is the prescient task of commercial providers to invent new products which switch the benefits accrued from existing providers to themselves, either inadvertently or deliberately, in the process creating a new range of marginalisations. For artists, all technologies represent potential methodologies whether new or old, and their preoccupations do not necessarily coincide with supposed majority interests in convenience and accesibility. When we reach for our iphones to record the everyday world we may not be overly troubled by the issues that surrounds our easy adaptation to new technologies – we might think it well worth the trade. But there are pertinent questions raised by the artists in this exhibition about self-expression, ownership and loss, which we might do well to consider.

Allan Parker – 20.02.2017